When housing production falls short where people live, work and play, the quality of life for all residents in our communities is diminished. The lack of quality, affordable housing can exacerbate social issues such as homelessness, poor educational attainment and mental and physical health conditions.

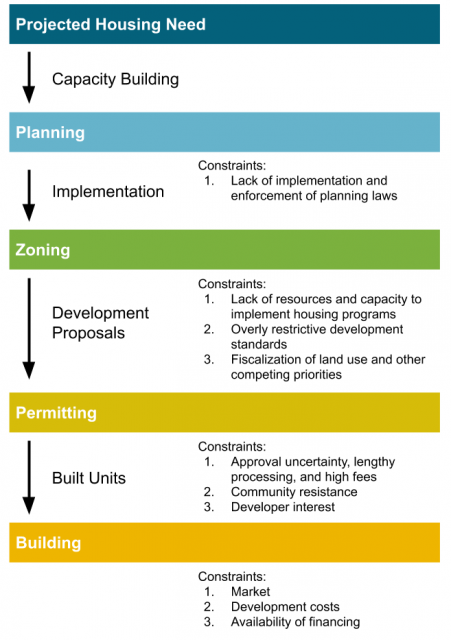

According to a recent survey by the state Department of Housing and Community Development, California will need to build 180,000 homes per year through 2025 to meet demand. Currently, approximately 80,000 homes are built each year. When housing supply does not meet demand, prices increase.

Awareness of California’s affordable housing crisis has increased exponentially in recent years as home prices and rents have skyrocketed, in many cases locking even middle-income families out of the housing market. For low-income families, the implications are even more severe, as they may be forced to forgo necessities or live in substandard or overcrowded conditions in order to afford shelter. The lack of housing supply is also one of the leading causes of homelessness across the state, as vulnerable populations struggle to compete for housing at the low end of the market.

For most communities, housing is much more than a place for residents to sleep at night. Collections of homes create social networks. Neighborhoods can be an important part of people’s identity and self-image. For some, it is also a financial asset, and often the largest single investment a family may have.

For communities of color, equalizing home-ownership rates in the United States can substantially impact the racial wealth gap decreasing the wealth gap by 16 percent for the Black-White wealth gap and 41 percent for the Latino-White wealth gap. As the housing crisis continues, it can exacerbate inequality by making it more difficult for historically disadvantaged communities to become homeowners.

While most everyone agrees that California needs more housing, the conversation often gets complicated when you begin to discuss how, where and why. And yet, it is the how, where and why that will shape our economy, our environment and people’s daily lives for decades to come.

The housing crisis is not a problem that any one group or community can fix alone. It will require the building industry and governments at all levels to work with residents to address the many barriers that prevent residential construction.

There are a numerous factors contributing to the lack of housing in California communities. One reason is the difficulty many city and county leaders face when planning and approving potential housing developments. Often housing proposals spark an emotionally-charged community debate centered more on differing values and a lack of trust than the factual merits and impacts of the housing project itself. Local elected officials and staff leadership then face an uphill battle, expending limited resources, which all too often leave all parties involved frustrated and divided.

Creating a Common Language

The cost of living is extremely high in California and ranks second in the nation behind Hawaii. High housing costs have far-reaching policy implications on the quality of life in California communities, including health, transportation, education, the environment, and the economy.

California is home to 21 of the 30 most expensive rental markets in the country. In fact, not one of its 58 counties has sufficient affordable housing stock to meet the demand of low-income households. Currently, the state’s 2.2 million extremely low-income and very-low income renter households are competing for just 664,000 affordable rental homes.

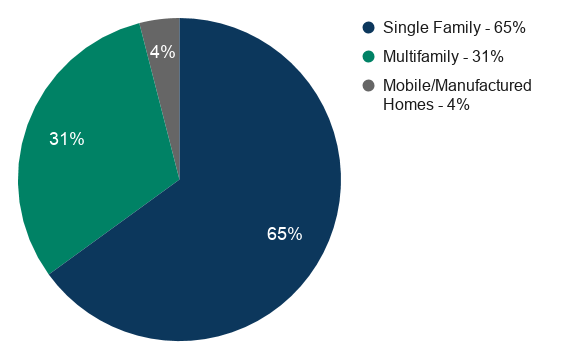

Figure 1.10: California Housing Stock by Type

2011-2015 Average: Multifamily, Single-Family, and Mobile/Manufactured Homes/Other

| Housing Type |

Total Number of Homes (million) |

| Single-Family (1 unit detached or attached) |

9.00 |

| Multifamily (2 or more units) |

4.32 |

| Mobilehomes/Manufactured Homes/Other |

0.53 |

| Total |

13.85 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, DP04 Selected Housing Characteristics. Original graphic by HCD.

There is currently a movement in California to make housing more affordable, but what does that actually mean?

According to the federal government, housing is “affordable” if no more than 30% of the monthly household income is spent on rent and utilities.

Housing advocates go a step further and define affordable housing as a situation where residents can afford a place to live that provides a sense of security and community, one that allows the resident to balance the cost of shelter with other necessary expenses in a way that does not continually cause stress or financial burden.

Yet, a broader definition of the term “affordable housing” describes an entire industry centered around the provision of this type of housing.

While many people immediately think of the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program as affordable housing, there are actually dozens of programs designed to make housing more affordable to various groups of people. These are five of the most prevalent types of programs in California:

Low Income Housing Tax Credit Program

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) is a tax credit for real estate developers and investors who make their properties available as affordable housing for low-income residents. The program is funded by the federal government, but administered by the state.

Housing Vouchers

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) provides rental subsidies through its Section 8 voucher program. People with vouchers live in apartment buildings or houses rented on the private market. They pay 30 percent of their income toward rent and give their landlord a voucher for the remainder, to be paid by the federal government. There are no limits on the rent the landlord can charge, but there are limits on how much the vouchers are worth, so vouchers are often not enough to make up the gap, especially in an expensive market like the Bay Area. As HUD dollars continue to shrink, and the waitlists for this type of housing grows so does the burden for state and local governments.

Public Housing

In the 20th century, the federal government actively built, owned and managed public housing through local public housing authorities. While public housing may have been created with good intentions, the flaws that plagued this program have shaped the way people think about affordable housing. Today, local housing authorities continue to own and manage existing properties, but the government is not building new units in this model.

Inclusionary Housing

Many local governments require developers of market-rate housing to make some units available at below market rate. Sometimes these units are provided on the same site, sometimes in a separate project, and sometimes the developer can pay a fee to fund another developer to build those units. Similarly, Oakland requires residential and office developments to pay impact fees that fund affordable housing. To live in inclusionary housing, potential residents must submit an application and, in some cases, enter a lottery to win a coveted spot. The developer is required to set rents at affordable levels and to verify that applicants both meet income requirements and can afford to pay those rents. Ultimately, the developer/owner pays the difference between the cost to operate the unit and the rents regulated by the city. They may, in some cases, pay the difference through securing funding from federal, state, or local affordable housing financing sources.

100 Percent Affordable Housing

Some developers specialize in building developments where 100 percent of the units are designated for people with low incomes. Primarily, but not exclusively nonprofit organizations, these developers specialize in assembling different funding sources from private and public entities.

What is Area Median Income (AMI)?

Each of these programs use a central statistic — the area median income, or AMI — to determine whether families are eligible for an affordable housing unit. The (AMI) is the household income for the median — or middle — household in a region. As a quick refresher, if you were to line up each household in the area from the poorest to the wealthiest, the household in the middle would be the median household. Each year, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) calculates the median income for every metropolitan region in the country. HUD focuses on the region — rather than just the city — because families searching for housing are likely to look beyond the city itself to find a place to live.

Conversations concerning AMI usually involve the distinction between three types of households. Households earning less than 80 percent of the AMI are considered low-income households by HUD. Very low-income households earn less than 50 percent of the AMI and extremely low-income households earn less than 30 percent of the AMI. This is very important for understanding how affordability takes on a different meaning in various communities throughout the state.

Designing a Sustainable Community

The rising cost of construction and flattening rents have made it hard to get projects off the ground. These factors can negatively impact the builders’ anticipated profits making it difficult to secure further investments from the private sector.

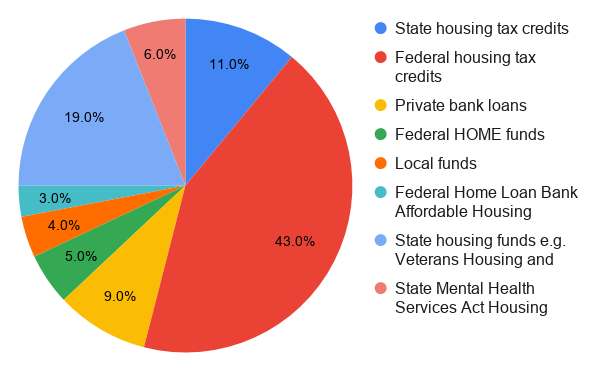

In many California Communities, local governments are struggling to convince developers to build market-rate housing, let alone affordable homes. For projects other than inclusionary housing, developers must pull together a set of government or philanthropic subsidies to cover the cost of developing the project. In some communities, developers need to coordinate government, philanthropic, and private subsidies to make an affordable housing development financially viable.

In rural communities, the construction crews are not always available, or willing to live remotely while a project is being developed. Additionally, it can take 12-36 months to finish construction on a housing project.

While local governments don’t build homes, they do have an obligation to plan and approve the housing that their communities need while minimizing delays, costs and barriers to housing.

More than half of the land in California’s municipalities is zoned for single-family homes. This type of housing has open space on all four sides and is detached from other structures. The benefits of this type of housing is that it offers privacy, land, storage and parking opportunities for the owners. Home builders and potential home-owners have preferred single family homes. For decades, the single family home has been a symbol of the American dream and has dominated California’s communities. However, these homes are often more expensive to build and utilize more land. As affordability problems become more acute, some cities are reexamining their planning and zoning practices, and seeking to include a mix of housing options to address affordability and environmental concerns.

Source: Examples based on actual development financing. Original graphic by HCD.

Multiunit housing, such as duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, townhomes, courtyard apartments and bungalow courts, share a common wall. As such, these homes do not offer the same level of privacy or space. However, integrating these types of homes into a community often serves the “missing middle” by providing a variety of affordable options that fit seamlessly into low-rise, walkable neighborhoods. Because these homes are cheaper to build, and therefore more affordable, they can provide families an opportunity to integrate and remain within the same community as their needs and income change.

Communities need various types of housing to thrive. In many cases, those that perform vital services don’t make enough money to live in the communities in which they serve. Workforce housing typically refers to housing that is affordable to households earning 60 to 120 percent of the area median income. This type of housing is targeted mainly at public employees including teachers, police officers and firefighters among others, who are integral to a community, yet who often cannot afford to live in the communities they serve. Although there is a large need for workforce housing in California’s urban and suburban centers, it is often some of the most difficult to build since affordable housing subsidies are not available for projects housing families earning more than 80 percent of area median income.

The missing middle concept helps frame a new conversation about housing, even in communities that are hesitant to explore “density” or “multi- family.” Robust and proactive discussions can be initiated by asking questions such as:

- “Where will your children live if they move back to the area after college?”

- “Where will empty nesters move when they need to downsize and be less dependent on a car?”

- “Where will community service providers, like teachers or police officers, live who have moderate incomes?”

Policy Decisions to Support the Missing Middle:

- Allow for duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes on all residentially zoned land.

- Strategically rezone land to allow for denser missing middle over 25 units per acre.

- Allow for higher lot coverage (75 percent or more) for missing middle products.

- Consider using maximum floor area or height instead of units/acre to regulate intensity.

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs), also known as second units, granny flats, or in-law units, are dwellings that exist on a lot with another house. ADUs can be built as detached units in the backyard, or as a garage conversion (attached or detached). An existing room within a house may also be converted into a separate unit. ADUs are a sustainable way to add flexible, affordable, and diverse housing options with minimal impacts on existing development patterns and infrastructure.

As California prioritizes equity and reducing greenhouse gases, the focus has turned to more-compact development that reduces sprawl (and many of its negative environmental and health consequences); however, targeting development to specific areas can put pressure on limited land and result in higher costs for a variety of reasons (infrastructure limitations, demand for limited land, etc.).

The true costs of sprawl are much higher when taking into account health impacts, environmental damage, and lost productivity, but these costs are often “hidden” from housing prices. There is also the potential to develop into the wild urban interface and/or into areas at risk of sensitive habitats, potentially putting communities at risk of living in a fire hazard zone.

Natural disasters and extreme weather events exacerbate the affordable housing crisis. Recent events like the fires in the North Bay, Butte, Ventura and Los Angeles Counties as well as the recent Ridgecrest earthquake, displace thousands of Californians each year. Although organizations such as FEMA and the Red Cross provide immediate assistance for victims of natural disasters, individuals already living in poverty or without support systems may not be able to find new permanent housing options. California communities are encouraged to develop a comprehensive mitigation approach based on a risk assessment. This can apply to both existing and future conditions, and can be addressed through regulations, local ordinances, land use and building practices, and with wildfire mitigation projects. Becoming a fire-adapted community provides a new frame in which to discuss housing issues in your community. For more information visit download the Wildland Urban Interface: Wildfire Mitigation Desk Reference Guide.

Regardless of the type of housing being built, local governments may face concerns and opposition from their community for various reasons. Engaging communities early and authentically can help assuage these concerns and generate more trust any buy-in. The sections that follow will discuss a number of potential community concerns and strategies to engage residents to address these concerns.